Opening Minds Evaluation, 2012

Executive Summary

The accountability movement in education reform has placed improving teacher quality and effectiveness front and center. Providers of professional development are tasked with developing and implementing professional development models that best meet the needs of teachers and others who work with young children and ultimately have the greatest impact on children’s learning and development.

Included in its professional development model, Opening Minds offers a four-day conference featuring professionals and presenters from around the world. The report describes the findings from a post-conference survey. The survey asked conference attendees to respond the statements that parallel the intended outcomes of professional development: knowledge, implementation, and change in practice.

A broad cross section of the early childhood workforce responded to the survey. The respondents were overwhelmingly positive about the effectiveness and impact of Opening Minds:

Introduction

This report presents evaluation findings from the 2012 Opening Minds conference. Opening Minds offers the largest early care and education conference in the Midwest featuring professionals and presenters from around the world. The four-day conference offered 300 workshops in fifteen different content areas and included opportunities to earn a variety professional development credits (see for 2012 Opening Minds Conference Program at ).

The purpose of the evaluation was primarily to examine attendee’s level of satisfaction with the 2012 Opening Minds conference. In addition, the evaluation focused on whether the conference was viewed by attendees as an effective professional development opportunity.

This report presents an overview of the current context of early childhood professional development, a description of evaluation methods, an analysis of evaluation results, conclusions, and recommendations for future evaluation of Opening Minds.

Professional Development in Early Childhood Education

This section offers a brief overview the current research in early childhood professional development. The purpose is to consider the Opening Minds in the broader context of professional development in early childhood.

The accountability movement in education reform has placed improving teacher quality and effectiveness front and center. In early childhood education, programs and teachers are increasingly tasked with ensuring every young child enters formal schooling “ready for school.” There is considerable debate around what this readiness entails and how best to achieve it, but most experts agree that high quality early childhood education experiences begin with a teacher who understands how young children learn and develop. What is less clear is how to ensure that all early childhood practitioners have this critical knowledge and understandings. The research evidence on the relationship between levels of formal education and teaching effectiveness is inconclusive. While there are studies that have shown that higher levels of education lead to improved interactions and effectiveness in early childhood classrooms (Winton & McCollum, 2008), there are also studies that found little relationship between teachers’ level of education and overall classroom quality or academic outcomes for children (Early et al., 2007).

A critical factor in a discussion regarding effective professional development in early childhood education is “who” provides early childhood care and education services. According to a 2008 report highlighting demographic characteristics of early childhood teachers, many early childhood teachers face difficulties in higher education programs because they lack the sufficient academic preparation for the rigor of college-level course work. Moreover, many lack the material and social resources necessary to support formal education pursuits: 19% live at least 200% below the federal poverty level, many have low literacy skills or low English language proficiency, most work long hours with few or no benefits (Kagan, et al. 2008) and have many have competing work and family obligations (Whitebrook, et. al, 2001).

The combination of inconclusive evidence regarding the impact of formal education and a workforce that faces significant barriers to formal education requires alternative approaches to professional development in early childhood education. Hawkins, et al. (2010) describe three professional development formats for providing training to in-service early childhood teachers. They include workshops, professional development schools, and on-site coaching and mentoring. On the surface, both professional development schools and on-site coaching and mentoring have the most potential as effective professional development formats. They both encompass quality components of training outlined by Hawkins, et al, 2010 and others. Further, there is evidence that the episodic workshop approach in the past has inadequately prepared early childhood teachers (Siberly, Lawrence, and Lambert, 2010).

However, while “who” early childhood teachers are has been documented and considered in the discussion regarding effective professional development, where they work and their role in the workplace has not been fully considered. The National Professional Development Center on Inclusion (NPDCI) in their 2008 review of the early childhood professional development identified six key assumptions needed to develop a conceptual framework for effective early childhood professional development. In the list of key assumptions, second only to the need to consider all formats (formal and informal) is the need to fully consider the ECE workforce – roles and organizational affiliation. The early childhood workforce constitutes a group of professionals who are widely diverse with respect to their roles (e.g., teachers, teaching assistants, family child care providers, paraprofessionals, disability specialists, consultants, family support providers, directors and administrators, etc.) and their organizational affiliations (e.g., Head Start, community or private child care center, family child care, and public school programs). When role and organizational affiliation are considered, professional development schools and on-site coaching and mentoring formats face significant feasibility issues.

A conceptual framework for early childhood professional development is emerging (NPDCI, 2008) and it can provide much needed guidance to interpret research on early childhood professional development and assess the effectiveness of early childhood professional development efforts (Sibley, Lawrence, and Lambert, 2010). This promising framework considers the who, what and how of professional development and interconnectivity among them.

Opening Minds provides a unique model for professional development in early childhood. The model goes beyond scientific research and quality standards to directly addressing the practice problems and challenges practitioners face. Based on sound adult learning theory recognizing that adults learn best when there are problems being solved, Opening Minds improves the effectiveness of the early childhood workforce by drilling down to the rudimentary knowledge and skills professionals need to solve their practice problems.

For the conference, Opening Minds, carefully designs each conference track to provide incremental professional development and enable attendees to determine the dosage and choose what’s most relevant to them in real time. Critical to this process is selecting the right providers of the professional development. Opening Minds utilizes an international network of individuals and organizations, expert to novice, to inform our decisions and program design, and to present one of the nation’s foremost continuing education experiences and continually evaluates presenter quality and effectiveness (see Appendix 1).

Methods

For purposes of this report, only one data source (participant survey) is examined and analyzed (see Appendix 2). The survey was developed by an advisory group to the Opening Minds conference and emailed directly to a group of conference attendees a week following after the conference. About 600 online surveys were sent. Ninety-seven surveys were returned and analyzed.

Survey Results

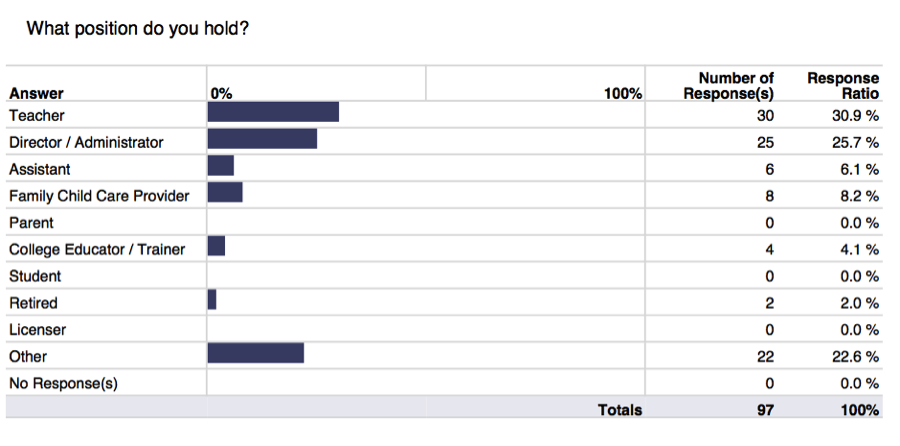

The first question on the survey asks respondents to describe their employment position. Table 1 shows the individual responses from the survey.

Table 1. Positions held by survey respondents

The data shows that a broad cross section of the early childhood workforce responded to the survey. As expected almost a third (30.9%) of respondents define their position as teacher, the largest sector of the ECE workforce. Almost a quarter of the respondents define themselves as other. This group represents the wide range of non-teaching professionals that are also part of the early childhood work force, such as nurses, librarians, early intervention specialists, parent educators, advocates, outreach coordinators, etc.

Two additional questions regarding what tracks respondents attended and which days they attended were also included in the survey. The responses from these questions show that all conference days and all content tracks are represented in the survey data.

Other questions asked respondents to rate statements regarding the “effectiveness” of the conference using a scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The statements parallel the intended outcomes of professional development: knowledge, implementation, and change in practice. The results of the survey are represented in percentages in Table 2.

Table 2. Responses to survey questions five, six, and eight

|

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly Disagree |

|

|

Opening Minds provided valuable knowledge to help me do my job better |

41% |

51% |

6% |

1% |

1% |

|

|

As a result of Opening Minds I tried a new idea or activity that had a positive impact in my workplace |

32% |

46% |

15% |

6% |

- |

|

|

Because of Opening Minds I changed practices that made me more effective at my job |

8% |

57% |

26% |

9% |

- |

|

The surveys results show that 89 respondents (92%) agreed or strongly agreed that the conference provided valuable knowledge to help them do their job better. More than three quarters of respondents (78%) agreed or strongly agreed that as a result of the conference they have tried a new idea or activity that had a positive impact in their workplace. Lastly, almost two-thirds of respondents (65%) agreed or strongly agreed that as a result of attending the conference they made a change in practice that they reported made them more effective at their job.

In an effort to gather more specific data regarding exactly which topics or conference sessions had the most immediate implementation impact, respondents were asked to identify an idea or activity from the conference that they tried out in their workplace. Sixty-seven respondents (69%) identified a specific activity or an idea. These responses were coded according to the content track they most closely fit (e.g. new apps for the Ipad was coded as technology track). The chart below represents the number of ideas and activities respondents implemented according content tracks. The total number of ideas and activities is more than 67 (number of respondents) because some respondents identified more than one activity or idea.

Table 3. Open-ended responses coded according to content tracks

|

Track |

Technology |

Administration & Program Operations |

Curriculum and Teaching Practices |

Social Emotional Development |

Family & Community Relationships |

Special Needs |

Nature |

Health & Wellness |

|

Number |

5 |

9 |

35 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

3 |

The majority (35) of the ideas and activities respondents implemented came from the curriculum and teaching practices track. Specific reference to training or staff training make up more than half of the implementation activities in the administration and program operations track. Other responses in the track were related to conducting training for staff or providing information at their center.

The survey also asked respondents how likely they were to recommend the Opening Minds conference to a colleague. Sixty-one respondents (63%) reported that they were very likely to recommend the conference to a colleague. Another 23 respondents (24%) said they were likely to recommend the conference to a colleague. Only two respondents said they were less likely to recommend the conference to a colleague.

The final question invited respondents to “add anything.” More than half of all respondents (53) made sixty additional comments that were analyzed and coded. From the analysis of the open-ended comments three distinct categories were identified. The categories were compliment, recommendation, and complaint. Almost half of comments (25) were coded as compliments. These comments were mostly general accolades such as “Excellent conference. Looking forward to next year,” “I enjoyed the conference tremendously” and “Thank you for another wonderful conference.” Other positive feedback focused on the quality of the presenters and presentations, opportunities for networking and one respondent wrote, “Opening Minds reinforces best practices.” Seventeen comments were coded as recommendations. Some recommendations included suggestions for additional sessions for school age, math, and early intervention. Most recommendations however, were related to conference format (e.g. shorter sessions, repeated sessions, fewer days, shorter breaks) and physical space (rooms closer together, more disabled friendly). Eighteen of the comments were coded as a complaint. Most of the complaints were related to conference logistics, such as rooms filling up to fast. There were just three concerns related to quality and type of sessions offered.

Conclusions

The diverse and problem-based professional development opportunities provided by Opening Minds clearly attracts a broad range of practitioners in early childhood education. More than one-third of survey respondents described their role with children and families as something other than classroom teacher, classroom assistant or center director. This group represented a very wide range of roles, including educators at the college level, librarians, early intervention specialist, and nurses. A review of professional development opportunities in Illinois reveals that Opening Minds is likely to be the only Professional Development model that appeals to such a wide range and successfully brings them together for a shared experience.

Survey respondents had a very favorable view of the Opening Minds, 2012. A strong indicator of satisfaction with any experience is whether or not you would recommend it to either a friend or colleague. In response to the question of how likely respondents were to recommend the conference to a colleague, eighty seven percent of respondents said they were either very likely (63%) or likely (24%) to recommend to the conference. Recommending the conference to a colleague may also show that not only were respondents “satisfied” with the conference, they may also feel that attending conference is good for their early childhood program. The open-ended responses at the end of the survey where respondents were asked “anything else” corroborate respondent satisfaction with the conference. Typically, this type of question elicits mostly suggestions and/or complaints, but almost half of these comments were compliments. The majority of the recommendations and complaints were related to conference format, not content quality of Opening Minds.

Additional data from the survey supports the conclusion that survey respondents believe the content of Opening Minds is not only good for them but also good for their early childhood programs. Ninety-one percent strongly agreed or agreed that Opening Minds provided valuable knowledge to help them do their job better. For the early childhood workforce, “doing my job better” should directly correlate to improved early childhood programs for children. Seventy-eight percent of respondents reported that they not only gained valuable knowledge, but they also used this knowledge to implement a new idea or activity at their workplace that they felt had a positive impact. Implementing a new idea or activity is a significant because it includes not only understanding a new practice or idea, but also believing in it enough to try it. Respondent’s willingness to try new ideas and activities from the conference was further exemplified in the number of responses to the open-ended question asking, “what idea or activity did you try?” Nearly 70% of all respondents identified at least one idea or activity on the survey. Analysis of these responses revealed that respondents were most likely to try an idea or activity that related directly to curriculum and teaching practices. Also important, was the analysis of the specific activities. Respondents are most likely in a short period of time to implement an idea or activity related that is concrete and content-specific. This finding is consistent with what (NPDCI) in their 2008 review of the early childhood professional development that professional development approaches focused on professional practices and consisting

of content-specific rather than general instruction are more effective. It also reflects the professional development goal of Opening Minds to provide practical solution in real time.

A third question asked respondents directly if as a result of attending the conference they changed practices that made them more effective at their job. An astounding 65% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed to this statement. This is important because changing practice as a result of professional development is not only essential for a teacher’s development, but reporting that change as improving their practice (making them more effective at their job) has implications for better outcomes for children. In short, the majority of respondents felt Opening Minds was not only informative, but also transformative.

Recommendations for continued evaluation of Opening Minds

The recommendations listed below are suggestions for an expansion of the evaluation of Opening Minds. The current survey data clearly shows that Opening Minds is an effective professional development program. Additional evaluation data will provide more insight into the success and impact of Opening Minds. In addition to continuing to align the evaluation plan with the desired outcomes for Opening Minds, consider the following recommendations:

- Expand the distribution of the post conference online survey to all conference attendees.

- Use onsite surveys to gather evaluation date from select workshops and presentations.

- Supplement both onsite and online survey with participant interviews.

- Gather feedback from presenters regarding the Opening Minds experience.

- Use survey data for additional outreach and feedback (e.g. email respondents to follow up on recommendations and suggestions from presenters and attendees).

- Continue evaluation of professional development provider quality and effectiveness.

References

Early, D. M., Maxwell, K. L., Burchinal, M., Bender, R. H., Ebanks, C. Henry, G. T., et al. (2007) Teachers’ education, classroom quality, and young children’s academic skills: Results from seven studies of preschool programs. Child Development 78, pp. 558-580.

Mitchell, A., & LeMoine, S. (2005). Cross-sector early childhood professional development: A technical assistance paper. Washington, DC: National Child Care Information Center. Available at http://nccic.acf.hhs.gov/pubs/goodstart/cross-sector.pdf

National Professional Development Center on Inclusion. (2008). What do we mean by professional development in the early childhood field? Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute. Available at http://npdci.fpg.unc.edu

Nelson, C., Main, C., and Kushto-Hoban, J. (2012). Breaking it down and building it out: Enhancing collective capacity to improve early childhood teacher preparation in Illinois. Chilcago IL: UIC College of Education.

Neuman, S. & Kamil, M. (2010). (Eds.) Preparing teachers for the early childhood classroom: Proven models and key principles. Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MY.

Sheridan, Susan M.; Edwards, Carolyn P.; Marvin, Christine A.; and Knoche, Lisa L., "Professional Development in Early Childhood Programs: Process Issues and Research Needs" (2009). Faculty Publications from CYFS. Paper 13. Available from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cyfsfacpub/13

Winton, P. J., & McCollum, J. A. (2008). Preparing and supporting high quality early childhood practitioners: Issues and evidence. In P. J. Winton, J. A. McCollum, & C. Catlett (Eds.), Practical approaches to early childhood professional development: Evidence, strategies, and resources (pp. 1-12). Washington, DC: Zero to Three.

Whitebrook, M., Sakai, L., Gerber, E. & Howes, C. (2001). Then and now: Changes in child care staffing, 1994- 2000. Technical Report. Washington D.C.: Center for Child Care Work Force.

Zaslow, M. & Martinez-Beck, I. (2006). Critical Issues in Early Childhood Professional Development. Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MY.